My last post began with the NSICOP report and a phrase that seemed tailor-made to undermine India’s dual concerns about credible threats of violence against Indian diplomats in Canada and Canada’s indifference to celebrations of violence in the name of Khalistan. Politicizing such an important report is disturbing, but it was not the first time it has happened. In 2018 the word “Khalistan” was removed from a National Security report despite, as Ujjal Dosanjh and Shuvaloy Majumdar wrote: “The issue of an independent Khalistan had been elevated to among the top five national security issues for Canadians.”

Instead of addressing the seriousness of that reality, our present government seems bent on lecturing India and proclaiming the superiority of Canada’s rule of law and system of governance. It is not to our favour that Canada’s 21st century attitude to India looks suspiciously like that of the 19th century British regime; those aristocrats and politicians who professed it was their duty (committed to posterity by Rudyard Kipling as The White Man’s Burden) to enlighten and redeem the unwashed masses of colonized countries. A better approach for Canada-India relations could be based on our shared history.

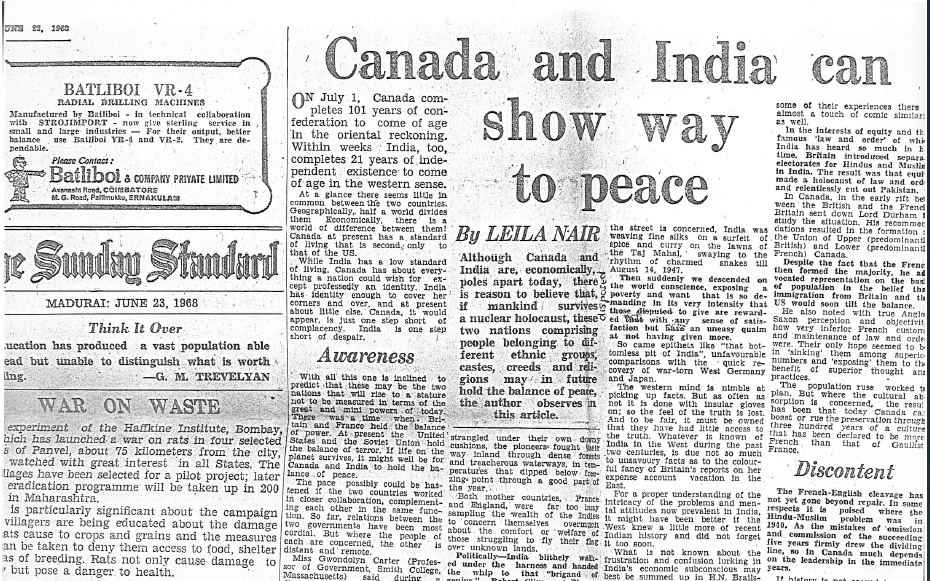

After immigrating to Canada, in an article carried by the Indian Express—Sunday Standard in 1968, my mother (Leila Nair, née Nambiar, 1931-2020) observed that Canada and India had much in common, formed as each was through Empire: “The War of the Austrian Succession and the Seven Years War were assiduously fought out on the banks of the St. Lawrence and the Ganga alike. The same personalities like Lord Cornwallis, Sir Charles Metcalfe and others have laid their stamp on the history of both.”

Both Canada and India were undermined by Britain before, during, and even after independence. For instance, Britain’s interference with Canadian efforts to build a profitable publishing sector creating lasting damage that Canada could not recover from. Terry Glavin reminds us that in 1872 our border with the United States was redrawn to American desires, through an arbitration panel agreed to by Britain and the United States (emphasis is mine). As was detailed years ago by our poet/constitutional scholar F.R. Scott (1899-1985), the British Privy Council continually “[forced] upon Canada the American type of constitution with its state residuary power, which we carefully and particularly avoided in 1867.”* And as far as India went; after looting, starving, and bankrupting the country, Britain’s parting gift was the assurance that religious division would undermine the nation from the very moment of its birth. As Shashi Tharoor (Member of Parliament, acclaimed author, and former Under-Secretary-General of the United Nations) wrote in 2017:

“Freedom came with the horrors of the partition, when East and West Pakistan were hacked off the stooped shoulders of India by the departing British. … When rioting, rape and murder scarred the land, millions were uprooted from their homes, and billions of rupees worth of property were damaged and destroyed. …. The creation and perpetuation of Hindu-Muslim antagonism was the most significant accomplishment of British imperial policy: the colonial project of “divide et impera” (divide and rule) fomented religious antagonisms to facilitate continued imperial rule and reached its tragic culmination in 1947.”

In the later twentieth century, there was ample ground for Canada and India to see each other as companions, to showcase cooperation, global citizenship, and human development during that tenuous time where nuclear annihilation was seen as a real possibility. Instead, Canada would only concede that it needed some Indian-born professional labourers. Again turning to my mother’s words of 1968, “Today, in the western mind, the gap between the India of myth and legend, and the India of the starving millions, is filled not by Robert Clive, but by Lord Mountbatten; not by Jallianwala Bagh, but by the Black Hole of Calcutta; not by the fact that by Churchill’s own assertion, for two centuries India supported two out of every ten in Britain, but that now she can no longer support herself.”

As disparaging as Canada’s view of mid-twentieth century Indian immigrants was then, a perception and conclusion far more damaging has replaced it. Canadians of Indian origin are assumed to be of one mind, a uniform voting block. In the eyes of all three major political parties, such a block aspires to the dissolution of India, claims as an ancestral right the fictional country of Khalistan, and conducts only peaceful protest in the service of their goals.

This would be farce were it not so painful. As I have detailed throughout this blog, Canada’s worst instance of terrorism was at the hands of those desiring Khalistan and plotting murder from within the safety of Canada. The total loss of 331 lives on 23 June 1985 could have been averted if, as was documented through a public inquiry led by retired Supreme Court Justice John Major, India’s many warnings had been heeded.

As to how Khalistani extremism took root in Canada, it is a complicated history that began in India but should resonate with Canadians. Years ago, Mordecai Richler described Canada as the outcome of the shotgun wedding of Upper and Lower Canada. Their union achieved Britain’s desires to save money and suppress the language, culture and dissent of French Canadians. In light of our origin story, the creation of India through partition looks like a shotgun divorce, with the family home that was Punjab casually torn apart and offspring unceremoniously tossed out of one side or the other.

Within that redrawn India, Punjabi Sikhs endeavored to secure greater recognition of their language and culture, and more local control in their region. But their ambitions did not include dismembering India. The Anandpur Sahib Resolution (1973), as documented by then-Justice R.S. Narula (1915-2005), makes it plain that the goal was not secession; instead, Sikhs desired to secure the dignity and well-being promised to all citizens by India’s constitution, regardless of religious affiliation.**

As tensions were rising in India, similar tension was already underway in Canada with respect to the province of Québec (formerly Lower Canada). Militant separatists, known as Front de Libération du Québec (FLQ), sought independence through violence. Bombings were frequent and James Cross, a British diplomat, was kidnapped in October 1970. A few days later, the FLQ kidnapped Pierre Laporte, a senior Quebec cabinet minister. While Cross was eventually released unharmed, Laporte was murdered.

That same theme of violence, but on a larger and more horrifying scale, would play out in India. Fanaticism and violence were harnessed to the goal of independence, ushering in a reign of blood and terror, all in the name of religion. The Golden Temple (the holiest site in Sikhism) became an armed fortress under the control of a puritanical preacher by name of Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale. He was not shy about ordering the disposal of people he did not agree with. Whether the victims were Hindu or Sikh did not matter.

At the time, Mark Tully (the BBC Bureau Chief in India) and Satish Jacob (an Indian journalist) were observing the deteriorating situation and the various efforts at negotiation. From Amritsar—Mrs. Gandhi’s Last Battle (1985), they quote Romesh Chander, a newspaper editor: “No one knows whose turn will come next. All of Punjab has become a slaughterhouse (125).” Shortly thereafter, Chander was murdered. In fact, Chander was the son of former editor Lala Jagat Narain who had also been murdered on Bhindranwale’s orders. That even Sikh clergy were not safe was underscored with the killing of Giani Pratap Singh (a former High Priest). The eighty-year-old scholar’s crime was his public criticism of Bhindranwale for storing arms and ammunition in the temple complex, and publicly stating that “Bhindranwale’s presence in the shrine was sacrilege (134).”

This period of history is complex and needs far more than a few paragraphs to address. Suffice to say it all led to a fateful day in June 1984 when then-Prime Minister Indira Gandhi set aside her prior unwillingness to violate the sanctity of the Temple Complex. In a military incursion known as Operation Bluestar, the Indian army was ordered to clear out the militants. While instructed not to fire on the Temple itself, severe damage was inflicted on the Complex. The casualty list was extensive, particularly with respect to civilian deaths. In retaliation, Gandhi was assassinated in November 1984 by her own Sikh bodyguards, which in turn set off a wave of fury across the region where innocent Sikhs were murdered while the authorities were largely indifferent to the slaughter.

In the aftermath, many Sikhs left India and many found their way to Canada. But some brought their hatred of India with them, to the dismay of Canada’s existing Sikh population. That community dated back to the turn of the twentieth century and had laboured, in every sense of the word, to build their lives here. They walked that fine line of integrating with Canadian society while retaining their culture and religion. While Canada was still largely disinterested in its brown-skinned population, there was growing respect and appreciation of Sikhism’s commitment to the wellbeing of all, its regard for the dignity of labour, and its principled stance on human rights.

In Sikhism, protection of the innocent is quite literally an article of faith. That Talwinder Singh Parmar (the architect of the Air India bombings) and his followers were so intent on murdering innocent men, women, and children, remains a grotesque betrayal of Sikhism. This is the legacy of Khalistan in Canada, even as Khalistan faded from prominence in both India and Canada.

As Kim Bolan wrote for the Vancouver Sun in 1997:

“Smoldering, dying, dead, drawing its last breaths. That’s how many Indo-Canadians describe the Khalistan movement — the struggle for an independent Sikh homeland that spilled over into Canada more than a decade ago and led to shootings, beatings, intimidation and the bombing of Air India flight 182, which killed 329 people. Today on the 12th anniversary of the Air India bombing, many Indo-Canadians, including some former Khalistan supporters, say the movement has lost support in Canada and abroad because of the violent tactics of certain groups … [The former president of the Ross Street Temple] admitted some Canadian Khalistanis turned people away from the movement by their violent actions, ‘There’s not much support here because the people who were fighting for Khalistan, they committed a lot of mistakes. They committed murders and robberies and all kinds of problems. … People were beaten up by the extremists here, by the Khalistanis.’”

Bolan’s assessment resembles the end of Canada’s own brush with militant separatism in Québec; after some 200 bombings, two kidnappings, and one murder there was little Québecois interest in the FLQ. While the movement for Québec independence continued, two failed referenda (albeit one by the slimmest of margins) further sapped the community’s interest in separation. Federal recognition of the distinctiveness of Québec society along with more allowances of provincial autonomy seem to have put the separatist agenda rest. (Although nothing is carved in stone.)

But I wonder, what would have happened if Québecois militants had been cheered on by citizens and politicians of other countries. What would Canada have said if foreigners regarded the murderer of Pierre LaPorte as a hero, a martyr, a noble leader? What would Canada have done, if calling for the assassination of Canadian diplomats was a routine occurrence in other countries? As I wrote last week, one sentence from Charles De Gaulle was enough to enrage Canadian leaders at the time, including then-Canadian Justice Minister Pierre Trudeau.

That the cause of Khalistan has attained a second life here is beyond disturbing. The first time, Canada ignored the rising extremism. This time, Canada is encouraging it.

But that ongoing history must wait for another day. June 23 approaches. For now let’s remember the Canadian families and friends we lost thirty-nine years ago, because of Khalistani terrorists in Canada.

Sculptor Ken Thompson

Cork, Ireland

* F. R. Scott, “The Development of Canadian Federalism.” Papers and Proceedings of the Canadian Political Science Association (1931): 231-47.

** G.S. Basran and B. Singh Bolaria, Sikhs in Canada (Oxford University Press, 2003)